Finding the “Design” in “Instructional Design”

Is the field of instructional design a design field? Would the study of instructional design (variously called “learning science,” “instructional systems design,” “instructional technology,” “educational technology” and so forth) benefit from being studied and practiced in ways more like other fields of design, such as architecture, product (industrial) design, and graphic design? I think so.

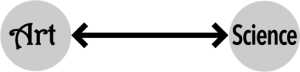

In the past I have asked instructional design students to tell me where they would place the field of instructional design on a continuum line with art at one end and science at the other. Some new designers put it closer to closer to art (“Everyone knows ‘teaching is an art’”) and some closer to science (“I think its more like engineering”). Most often they put it smack dab in the middle (“Just to be safe…”)

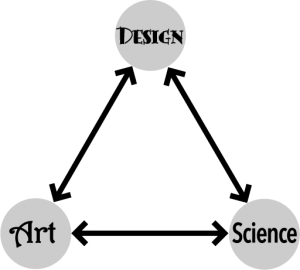

It a very hard question because, I believe, instructional design, both in study and practice, doesn’t really belong on that continuum at all. It’s closer to something both inclusive of and foreign to both: design.

The purposes of science is discovery of the natural world through experimentation and observation. Often the results of science have practical uses, but that is not its primary motivation. Its primary purpose is the discovery of knowledge or understanding. Art, on the other hand, is the study of aesthetic quality for personal and public expression and gratification. As with science, it may have practical value, but that is not necessarily its intended purpose. The purpose and motivation of all design fields, however, is practical. When done well, design incorporates both discovered knowledge and expressive aesthetics, but employs them to practical ends.

For example, consider architecture. There is clearly science involved: buildings use scientific knowledge to insure that they are built to be safe and to last. A whole plethora of sciences are involved in this: physics, chemistry, mathematics—even anatomy. Most of these are represented by science’s practical cousins, various kinds of engineering, materials science, ergonometry, etc. On the other hand, architecture is usually considered an art, especially when viewed historically. In any case, the process of doing architecture is not merely applied science, nor is it applied aesthetics. It is the processes of coming up with the best balance of both—as well as other things. That complex balancing process is called design.

In that way (and, I would contend, in others) instructional design is clearly a design field and study. If that is true, consider these questions:

- Why do instructional design theorists so often couch their work in scientific terms (e.g., “learning science,” “instructional science”)? Do we, like other social and “soft” sciences, have a severe case of “physics envy”¹?

- Why are instructional designers not trained in the tools other designers use to accomplish their work, such as sketching?

- Is it possible that instructional design theories and models would be put to better use if considered through a more “designerly”² perspective?

I’m hoping to answer some of these important questions.

Footnotes

(¹) first coined by Joel E. Cohen (1971) in a book review found in Science, May 14, 1971 (vol. 172), in which he wrote, ‘Physics-envy is the curse of biology.’

(²) see Cross, Nigel. (2003). Designerly ways of knowing. London: Board of International Research in Design.

(Cross posted at www.inquisitiveDesign.com.)

© Copyright 2012 by S. Todd Stubbs. All rights reserved.